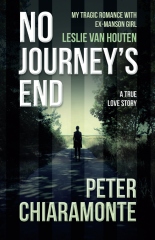

No Journey’s End, a new, “creative nonfiction” book by PeterChiaramonte, should best be enjoyed with a background soundtrack of Steppenwolf’s

classic, rock & roll anthem, “Born to be Wild.” Chiaramonte takes us on a

ride that perpetually seems to be heading over an existential cliff as he

recounts how his life-path intersected for a time with that of a convicted member

of Charles Manson’s murderous “family,” Leslie Van Houten. We follow the

journey of Chiaramonte as an aspiring but rebellious academic who chafes

against the reins of the traditional academy that leads him from an uninspiring

job in a suburb of Toronto to the psychedelic adventure that was Southern

California in the early 1970s. After seeing newspaper pictures of the then

young-and-beautiful Leslie Van Houten, he is compelled by an irresistible drive

to pursue, woo, and win the heart of a woman whom we know is ultimately doomed.

The author portrays Van Houten as a naif, caught up through little fault of her

own in Manson’s vengeance project driven by the sex-and-drugs-enabled mind

control of his followers. Throughout the hard-driving narrative, a variety of

characters from both Van Houten’s and Chiaramonte’s lives act as crash barriers

for the tragic couple careening towards the inevitable end. It is no spoiler

that would threaten the sheer roller-coaster enjoyment of the read to note that

Chiaramonte managed to veer safely to a life-long academic career, while Van

Houten has spent nearly her entire life in the maw of the US penal system.

No Journey’s End, a new, “creative nonfiction” book by PeterChiaramonte, should best be enjoyed with a background soundtrack of Steppenwolf’s

classic, rock & roll anthem, “Born to be Wild.” Chiaramonte takes us on a

ride that perpetually seems to be heading over an existential cliff as he

recounts how his life-path intersected for a time with that of a convicted member

of Charles Manson’s murderous “family,” Leslie Van Houten. We follow the

journey of Chiaramonte as an aspiring but rebellious academic who chafes

against the reins of the traditional academy that leads him from an uninspiring

job in a suburb of Toronto to the psychedelic adventure that was Southern

California in the early 1970s. After seeing newspaper pictures of the then

young-and-beautiful Leslie Van Houten, he is compelled by an irresistible drive

to pursue, woo, and win the heart of a woman whom we know is ultimately doomed.

The author portrays Van Houten as a naif, caught up through little fault of her

own in Manson’s vengeance project driven by the sex-and-drugs-enabled mind

control of his followers. Throughout the hard-driving narrative, a variety of

characters from both Van Houten’s and Chiaramonte’s lives act as crash barriers

for the tragic couple careening towards the inevitable end. It is no spoiler

that would threaten the sheer roller-coaster enjoyment of the read to note that

Chiaramonte managed to veer safely to a life-long academic career, while Van

Houten has spent nearly her entire life in the maw of the US penal system.

Given Chiaramonte’s credentials, it is not surprising that

this book can be read as a philosophical and existential reflection on one

person’s inexorable attraction to impending disaster. The narrative is filled with

drugs and rock-and-roll that typified the times (although notably, very little

sex). It is also filled with fast cars and the vicarious horrors that were the

crime scenes, both physically in the LaBianca and Tate/Polanski homes, and in

the psyches of the drug-deranged family members. During the prison visit scenes,

in which the author speaks with the object of his desire through bullet-proof

glass, one gets the impression that he is actually looking himself in a

Narcissus-inspired mirror. Zeus, it is humorously said, advised Narcissus to “watch

yourself.” Chiaramonte is given the same advice throughout the book by various

and sundry actors that populate both his and Van Houten’s lives. As the reader vicariously

races through the hell of the Manson experience in the author’s “shotgun seat,”

often watching the blur of scenery through spread fingers of hands over eyes, one

realizes that among many other things, No Journey’s End is a cautionary tale that

retrieves the ancient trope, there but for the grace of God go I. Chiaramonte

does a masterful job reflecting on what might – but could never – have been, looking

for adventure, taking the world in a love embrace, and exploding into space.

No comments:

Post a Comment